Origins of Artisanal Watchmaking Part I: The English Have Landed

The English Have Landed

The phenomenon known as ‘independent watchmaking’, or what we refer to in this exhibition as ‘artisanal watchmaking’, can arguably be traced to George Daniels (1926-2011). Daniels was an English watchmaker whose rise to prominence began as the English watchmaking industry – once the world’s greatest until the 20th century – began its terminal decline.

Daniels’ fascination with all things mechanical – his hobby was restoring and racing vintage Bentleys, something that watchmaking paid for – propelled him to become the most prominent horologist of the late 20thcentury. Though Daniels is best known in the wider world as the inventor of the lubrication-free co-axial escapement that he sold to Omega and which the brand successfully industrialised and commercialised throughout their collection - he was also exceptionally influential in high-end artisanal watchmaking.

An immensely talented maker of watches in the literal sense, Daniels had mastered 32 of the 34 disciplines required to craft a watch by hand, a process more commonly referred to as ‘The Daniels Method’ and which he detailed in a seminal book he authored – ‘Watchmaking’. Just as the world’s mechanical watch industry was being decimated during the Quartz Crisis of the 70’s and ‘80’s, Daniels in turn inspired a generation of subsequent watchmakers, including notables like Francois-Paul Journe. In fact, he held such deep admiration for Daniels that Journe gifted him one of his own wristwatches in 2010, a Chronometer Souverain with its balance cock engraved “FP to George Daniels, my Mentor”.

But like many watchmakers before and after, Daniels himself was inspired by Abraham-Louis Breguet, perhaps the greatest watchmaker of all time. In style and substance Daniels’ work was instantly recognisable as being derived from Breguet. Daniels’ famed Space Traveller’s watch for instance, was not just inspired by Breguet’s double-wheel escapement, but also based on the design of a trio of 19th century Breguet pocket watches, namely numbers 2807, 3862, and 3863, all of which have a similar, symmetrical, twin-display layout.

Daniels’ success as a watchmaker was also made possible by his patrons, who included collectors like Seth Atwood (1917-2010), an American industrialist who inherited his family’s automobile hardware business. One of world’s most important watch collectors in the late 20th century, Atwood purchased several watches from Daniels, including the only watch Daniels ever made on commission from a client.

Atwood even had his own watch museum (The Time Museum) in his hometown of Rockford, 90 minutes by car from Chicago. But as is often the case with great collections, the museum shut after his death and the watches dissipated at auction.

Much of Daniels’ accomplishments were realised with the help of his peers. And amongst his peers, none was as important as Derek Pratt (1938-2009). An Englishman like Daniels, but one who resided in a village outside of Zurich for most of his working life.

The Unusual Swiss Brit

Described as “George’s greatest horological friend” by David Newman, the chairman of the charity established by the Daniels estate, Pratt would long-distance dial and dialogue with Daniels every Sunday morning by telephone. Their relationship was tangible as well: Pratt had consulted Daniels on his numerous inventions and produced components for many of Daniels’ watches, although his contributions were never formally acknowledged by Daniels.

Despite widely regarded as an equal of Daniels in technical prowess - in his autobiography Daniels himself pronounced Pratt “an accomplished technical watchmaker in the true sense [who] can make every component of a watch from raw material” - Pratt is hardly known outside the closed coterie of connoisseurs, which is why his influence in the broader industry is circumscribed.

Pratt was a restorer par excellence, a scholar and published author in all things horological. A kind and modest man according to all who knew him – explaining in part his obscurity - Pratt was in many ways the stereotypical independent artisan who spent his lifetime working for others. This also explains why his name has no prominence on watch dials (at least not yet!). Pratt is now best known for the work he did for Urban Jürgensen & Sønner (UJS), an 18th century Danish brand that was revived in the 1970s by Swiss vintage watch dealer Peter Baumberger (1939-2010). The brand’s renaissance and subsequent success with collectors in the 1980s and 1990s was no doubt helped by Pratt’s skill and talent.

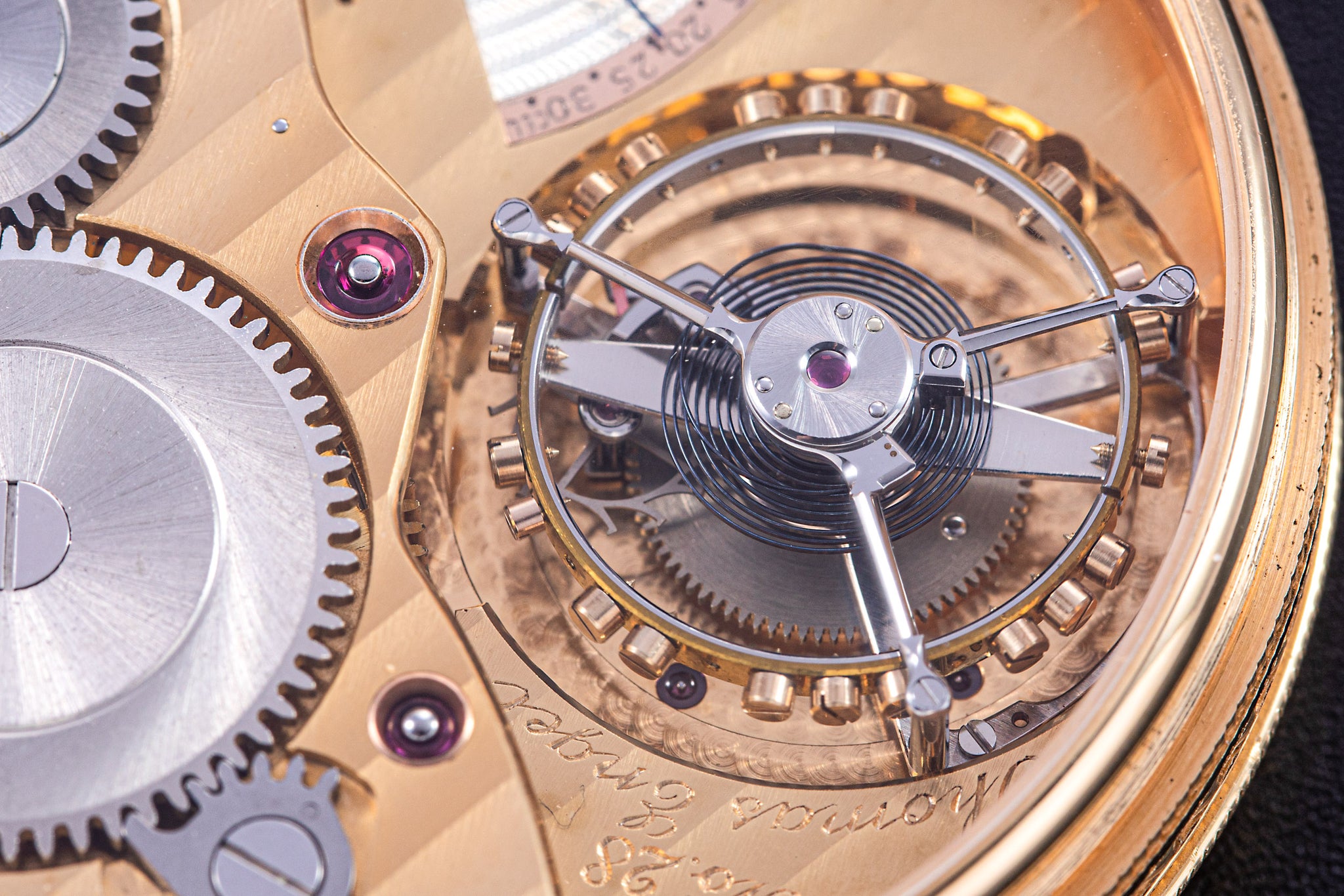

Pratt not only designed several of the complication mechanisms for its wristwatches, produced many of the guilloche dials, he was also responsible for building the brand’s tourbillon pocket watches. And as it was with the work of Daniels, the house style of UJS was very much Breguet inspired.

A Swiss-German Connection

Perhaps more interesting as a collector was Dr Thomas Engel (1927-2015) who started his professional career as a dishwasher for the occupying American army in post-war Germany. His fascination with plastics and a versatile, inventive mind eventually led to his claim over 120 patents, many in the field of polymers – inventing cross-linked polyethylene (PEX) that’s widely used in pipes and cables - but also the under-soil heating of the Munich Olympic Stadium.

Those inventions made him a millionaire many times over, and Engel lived life fully, having been married thrice. But his true passion was watches, particularly those of Breguet. Engel not only published a book dedicated to his Breguet collection, but also produced watches in the style of the French watchmaker as a second career.

Already middle aged, Engel moved to Switzerland to study watchmaking with Richard Daners (1930-2018), a talented Swiss watchmaker who worked for Swiss jeweller Gübelin for most of his career.

Daners not only taught Engel the craft, but also helped produced most of Engel’s timepieces, which were mostly finely crafted pocket watches powered by observatory chronometer-quality movements obtained from Zenith, but also included several Breguet inspired carriage clocks. Many of the pocket watches incorporated a tourbillon regulator featuring a distinctive three-armed carriage and open-worked cock, and a handful were even fitted with a thermometer driven by a bimetallic strip, just as found in some Breguet pocket watches.

Contemporary British Watchmaking

All of the gentleman who were crucial figures in late 20th century independent watchmaking are no longer with us; only their timepieces remain. Daniels’ legacy, however, lives on in Roger W. Smith

Having been hand-picked as an apprentice of the famously prickly Daniels in 1997 – Daniels had rejected all apprentices before - Smith was instrumental in helping Daniels complete the Millennium series of watches powered by Omega’s co-axial movements, a three-year project that ended in 2001. After which he was largely responsible for the development, construction and production of Daniels Anniversary launched in 2010 and which a decade later, has yet to be fully delivered.

Smith not only learnt the skill of making a watch by hand from Daniels but also inherited the Daniels mantle of English watchmaking – quite literally, as Smith now works out of Daniels’ workshop on the Isle of Man. Since 2001, Smith produced wristwatches under his own name, and like the first generation of contemporary artisanal watchmakers, very much in the style of Daniels and Breguet before him.

As traditional watchmaking in Switzerland was seemingly coming to an ignominious end in the 1970s during the Quartz Crisis, a handful of individuals were doing their bit to keep things going. Whilst brands such as Patek Philippe and Rolex had visionary leaders at the helm and who held firm to the ideals of mechanical watchmaking, there were also several stubborn artisans with an independent streak as well as mechanical talent. All began their careers modestly, but a handful grew in stature, becoming pioneers in what is today referred to as independent watchmaking.